Central Asia Part 6: Cycling along the Afghan border

Tajikistan: Pamiri culture in the Wakhan Valley (54)

We are in Khorog (30'000 inhabitants), the capital of the Autonomous Province of Gorno-Badakhshan in Tajikistan. We’re now back in lower altitudes at just over 2000 m and are experiencing pleasant, mild autumn temperatures and blue skies. It’s already a huge contrast to the barren Pamir plateau where we’ve been traveling the last few days. We were actually looking forward to Khorog, because there is a range of restaurants and nice homestays. But we would’ve been much more excited about reaching this little town, if we’d cycled all the way here. However, the hub break in the high mountains of the Pamirs made this impossible and so we had to take a cab from Murghab to Khorog (read more about this adventurous trip in our last blog No. 53).

Khorog is located at an important road crossing between the M41 (the original Pamir Highway) and the Wakhan Valley, making the town a stopover for all travelers along the Pamirs. Here one buys supplies again, exchanges information about the road conditions and enjoys the small selection of restaurants before heading into the solitude of the eastern Pamirs. In addition, the small town has a certain flair by Central Asian standards. But Khorog is also important for the residents of the Pamirs, as many come here to study at the University of Central Asia.

We see many young men in dapper suits and women in a mixture of western and traditional clothing. White sneakers, tight jeans and the traditional two braided pigtails dominate, but some also wear the elegant Pamiri attire with the white dress and the embroidered red cap. The young people here speak good English and seem very open and interested. There is even a small café in Khorog where people meet and it seems really modern compared to everything we’ve seen so far in Tajikistan. The contrast is extreme and we can't appreciate all the comfort yet, because we haven't finished with the Pamir in our minds. Therefore, we take a break in Khorog to make new plans for our remaining time in Tajikistan.

We order an expensive replacement hub from Germany, the beginning of a surprisingly long odyssey. The rear hub has to be manufactured especially for us and should arrive in Dushanbe around mid-October. The idea is to cycle the last part through Tajikistan to Uzbekistan with the new hub and then take a little break from our bike trip and leave the bikes in Samarkand. Since we have to wait a few days for the new hub, we have some time to explore more of Tajikistan, the only question is where to go and with which means of transport.

It’s clear for both of us that we’d like to see and experience more of the Pamir. We were too abruptly forced to leave the barren mountain world and it feels like something is missing. We would be very interested in visiting the Bartang Valley and the Wakhan Valley and we ask at the helpful PECTA office if fellow travelers would be interested in sharing a jeep for a roundtrip along the Pamir in early October. Of course, there aren’t any other travelers around and since one pays for the jeeps per km and of course also has to pay for all the accommodations & meals for the driver, this option unfortunately blows up our budget. We need a new plan.

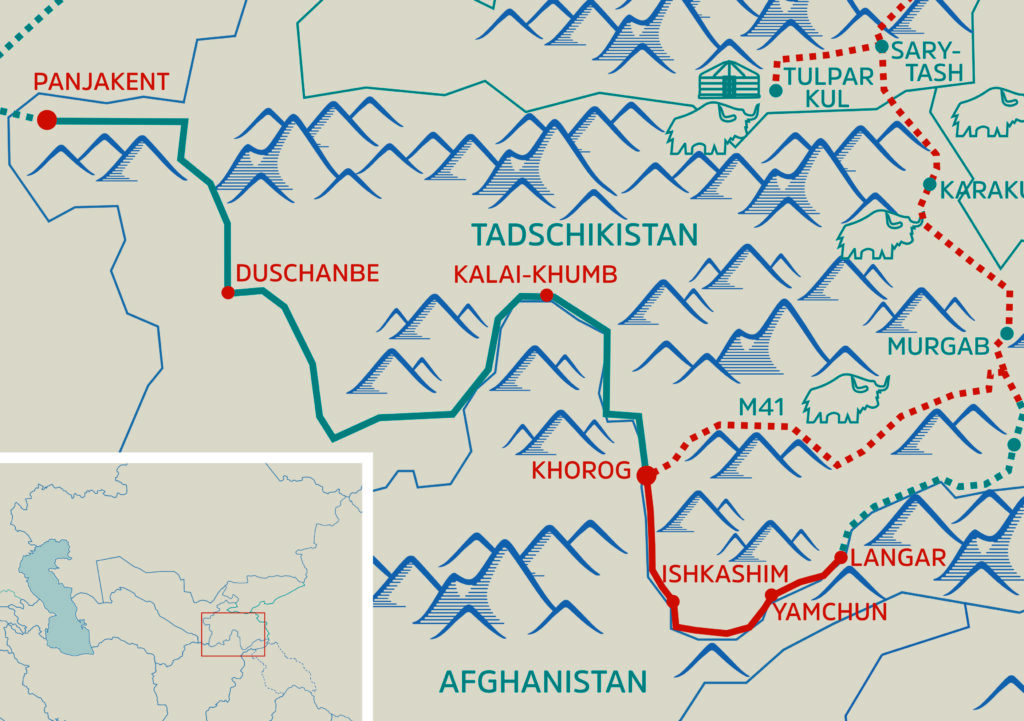

We contact various guesthouse owners and tour operators and find a touring bike at the popular Pamir Lodge, which we are allowed to rent for USD 10.- per day. Thus, we are free and can still see a little more of the Pamir, although not too hard stages, as we don’t really trust the rental bike. We decide to follow the Wakhan Valley along the Afghan border and take a week for it, because we want to learn as much as possible from the local culture. The whole distance from Khorog to Langar is only 216 km, but about 3500 meters of altitude and it'll be more exhausting than we thought.

Cycling the impressive Wakhan Valley along the Afghan border

We buy as many fresh products as we can find at the local bazaar in Khorog, leave a part of the luggage and the broken bike in the hotel and set off through the Wakhan Valley. The first few meters I feel light as a feather without the two front bags and I can easily ride away from Dario on the first climbs. A completely new feeling to be on the road with such a light bike, but I miss my Brooks saddle and it’s not very comfortable. Therefore, better to focus on the beautiful surroundings.

As soon as we leave the last houses of Khorog behind us, we look at Afghanistan for the first time and it’s so incredibly close that we can wave to the people on the other side. The crisis-ridden country seems completely peaceful in this corner. In the fertile plains in front of the imposing peaks, the men are tilling their fields and the children are playing soccer. The women wear flowered headscarves and dresses, no burqas far and wide. When I see a young Afghan woman washing her clothes in the cold border river Panj, I wave to her and we smile briefly at each other. A goosebump moment. So much separates us and yet we are connected for a short time in this one smile just between women.

But this peaceful picture and the beautiful landscape can’t hide the harsh reality of life on the other side. Although here in Tajikistan we’re already in a very remote corner with little infrastructure and dusty roads, it’s no comparison to Afghanistan. There, there are only steep, unpaved roads and no electricity. Few trucks torture themselves laboriously meter by meter forward, but only very few locals own a car and we observe many people who travel for kilometers on foot or by donkey.

We see armed men in a jeep only once on the Afghan side. This corner is too remote to control the whole border area. Nevertheless, I hold my breath, because after all, I'm riding a bicycle just a few meters away from them with a T-shirt and without a headscarf. Everything highly forbidden on the other side. While riding along the border we can’t help but to constantly think about how different the lives of women are on these two sides. The women in Tajikistan study in the cities and have the opportunity to work outside their homes and it’s accepted by society. They are oriented towards the West, Russia or China and yet they still hold on to their traditions. But they seem free and unattached to us. Of course, that isn’t the whole picture either, we are aware of that. But it’s a huge difference from the life of women in Afghanistan who aren’t allowed to visit schools. To feel so powerless in the face of these constant injustices on this journey hurts us again and again.

What we see on the other side is the Wakhan Corridor in Afghanistan, a strip of land 270 kilometers long and in places only 15 kilometers wide, far from any civilization and day's ride from the nearest health clinic or school. The narrow land sits at the convergence of three of the world’s major mountain ranges: The Hindu Kush, the Karakorum and the Pamirs and it’s about as far away from the noise, traffic and muezzin’s call to prayer of urban Afghanistan as you can get. The Wakhan Corridor is a relic of the Great Game between Britain and Russia for supremacy in Central Asia in the late 19th century. It was established in 1893 as a buffer zone between British India on the one hand and Russian Central Asia on the other. The corridor is closed to regular traffic and there is no road connection east towards China, somewhere in the middle of nowhere the path simply ends. The isolated region has been barely touched by the hands of times and has remained surprisingly peaceful and some of the locals weren’t even aware of the war going on in their own country.

The Pamiri Culture: Similarities on both sides despite the border

The inhabitants on both sides of the border river are Wakhis and belong to the Pamiri ethnic group. They inhabit not only the Wakhan Corridor, but also Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan and it’s estimated that the total number of Wakhi people would be around 70,000 to 100,000.

They obviously have more in common with the culture of the inhabitants of the Wakhan Valley in Tajikistan than with the rest of Afghanistan and speak the same language and have similar habits, no wonder when living in the same climatic conditions and so isolated. It wasn’t until the creation of the Wakhan Corridor that the Wakhis were separated from each other and it again brings to our attention what artificial constructs borders actually are. Later, when we see a documentary about Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan, we realize how close the culture is and can now better imagine what it would’ve been like to cycle through the north of Pakistan as it was originally our plan.

Before the Covid pandemic, there was a lively exchange between the two sides at the weekly border markets held at Ishkashim, Khorog or Kalai-Khumb. One was allowed to visit these even as a tourist without an Afghanistan visa. In general, the Wakhan Corridor was the only corner of Afghanistan that was relatively safe to travel as a tourist in the years before the pandemic. Extremely beautiful and culturally interesting, but one has to be prepared for even more adventure and comfort sacrifice than in Tajikistan (see the documentary "Backpacking Afghanistan”). All this is now unfortunately no longer possible. We’d also be curious to not only see the other side, but to experience it. Maybe one day.

As we cycle on bumpy roads along the Afghan border, we keep passing Tajik soldiers and checkpoints where we have to show our passports and indicate our route. A 2-year military service is mandatory in Tajikistan and here the young men seem to be tasked with walking for hours along the border river with their rifles. They seem extremely bored. Of course, every now and then a military exercise may not be missing and then the road is closed for a short time, because tanks are shooting into the mountains. We don't feel that comfortable. But we prefer to concentrate on the impressive landscape and the encounters with the people in the Wakhan Valley.

Only here we really experience the hospitality for which the Pamiris are famous for and are literally greeted by everyone, smiled at and invited for chai. The children line up and greet us with strong handshakes as we pass through. We keep smiling and are strongly reminded of Iran, also because of the language as Tajik belongs to the Persian language family and it’s much easier for me to communicate than in Russian, a language which I struggled with the past weeks.

The inhabitants of the Wakhan Valley are real linguistic talents and all speak their own dialect, Tajik as lingua franca and in addition Russian and sometimes English. Each valley seems to have its own language and Shughni and Rushani are the most spoken Pamir languages. The cultural and linguistic diversity of the Pamir Mountains is enormous and in total there are about 100,000 native speakers of a Pamir language. They are mainly used orally, while Tajik is used throughout the Gorno-Badakhshan province as a written language in school and for official affairs.

While we were traveling in a narrow gorge between Khorog and Ishkashim and very close to Afghanistan, the scenery changes completely after the main town of Ishkashim. The border river Panj is much wider and branched here, but the view is even more spectacular. But it’s also more exhausting than expected and I’ve been sick since Murghab and don’t seem to get any better. Somehow my body can’t tolerate the Tajik food, which makes cycling even more tedious. I often already get sick at the mere thought of the unappetizing Shorbas that await us in every restaurant. Fortunately, we have our tent and some supplies with us and can cook for ourselves. There aren’t that many camping spots in the Wakhan Valley, but if you ask, you can easily pitch your tent next to a field. Usually we even get invited by the families to stay in their house. Unfortunately, we can’t accept these invitations as I’m feeling too sick.

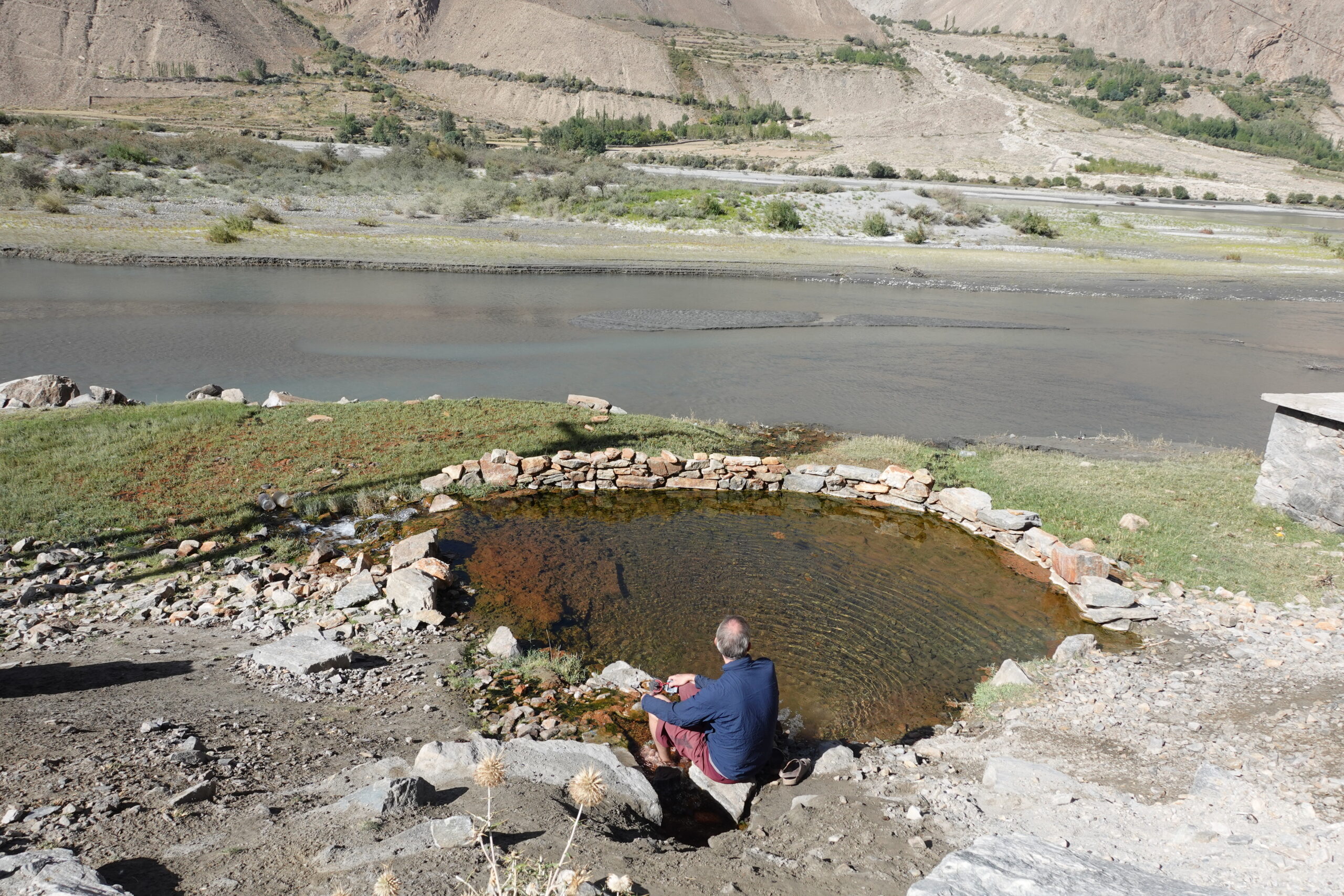

Already in the first two days we realize that the journey along the Wakhan Valley was worth it, as it gives us again a completely different impression of the Pamir. The landscape is lovelier, the climate milder and the trees are fading from green to yellow and we’re blessed with beautiful autumn colors. Dust from the wheat harvest fills the air as the locals are preparing for winter. We cycle along hot springs, dilapidated forts and enjoy the view of the high mountains of Afghanistan and then we even come across sand dunes. It’s simply stunning.

Old fortresses, hot springs and hospitality in Wakhan

The Wakhan Valley was once a section of the Silk Road and there are still numerous ruins of caravanserais, fortresses and even some Buddhist stupas can still be discovered in the valley. One could spend a complete week exploring the Wakhan Valley, as there is much to see and also some interesting day hikes. As cyclists we make only a few such stops at a time, as the journey itself is demanding enough. However, we decide to spend two nights in the village of Yamchun (3030 m), which has two attractions at once: the hot springs of Bibi Fatima and the Yamchun Fortress, the best-preserved fortress in the Wakhan Valley. The fortress was built in 300 BC and has a spectacular location overlooking the Wakhan Valley and the high mountains of the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan.

But not only the fortress and the hot springs are worth the visit, but also Akim's homestay, which sticks to the hillside and can only be reached by a steep path. On the way, we chat with the villagers as best we can. The faces of the locals are all marked by wind and weather. An old woman gives us her bread, resistance futile. She lives in a typical one-story Pamiri House made of plastered stone, with a flat roof on which hay, apricots, mulberries or dung is dried for fuel.

We push our bikes further and further up and are finally greeted with a smile by Akim himself. Together with his wife he runs the homestay, the three children all live in the cities. We spend the night in a simple room on the floor. The very improvised shower and toilet are outside. Every time I wash my hands I get a slight electric shock, there was probably a little too much improvisation by Akim. But when you are on the road at the Pamir, you are grateful for every warm shower, even if it sometimes tingles a bit on the skin. But the homestay itself is very cozy and there is really good homemade food from their own garden.

We're finally able to enjoy food again and even the daily Plov excites us for the first time. Akim proudly shows us his spacious garden. Most of the inhabitants of the Wakhan are self-sufficient, which also explains why you’ll only find dry cookies and pasta in the small stores, just what is in demand, since all fresh produce grows in the garden. Apples, tomatoes, pears, lettuce, cucumbers, potatoes and onions thrive here. And of course, the typical bread oven in the garden can’t be missing. After dinner we drink tea in the warm living room, play with the cats and listen to Akim commenting on the American TV channels he likes to watch. We feel like we’re taking a break at our grandparent’s house.

A house full of symbolism

Adjacent to the spacious living room at Akim is the typical Pamiri House, full of symbolism from Zoroastrianism and Ismaili Islam. The exterior of the house is painted white and the interior consists of one spacious room full of carpets in red colors, the color of the sun and fire. On each side of the room are four raised platforms, which serve as living and sleeping quarters, and in the center is a skylight that was once used as a smoke outlet and now allows light into the usually rather dark room. The decorative wood carvings are the same in each Pamiri house and each pillar and element in this room has its meaning. It's an honor for us to enter such a traditional Pamiri house and we are surprised to learn that Akim and his wife still sleep here.

The majority of Pamiris are Ismailis, who belong to the Shia branch of Islam. Their spiritual leader is the Aga Khan, the 49th Imam of the Ismailis and religious leader of approximately 15 million people. You can find his picture in every Pamiri home, although he hasn’t been in Tajikistan for a long time and has his main residence in Switzerland. However, his Aga Khan Foundation is important for the development of remote Gorno-Badakhshan and also one of the largest private NGOs in the world. The Ismailis practice a progressive Islam that places a high value on education. Women don’t wear burqa and there are no mosques, but community halls for praying instead.

The roots of the traditions in the Pamirs are older than Islam and lie in Zoroastrianism and shamanic practices. Again and again, we pass holy shrines, which are often decorated with the horns of the Marco Polo sheep or built from special stones and are usually located near sacred springs or trees.

After eight days of cycling, we reach the village of Langar, for us the end of the Wakhan Valley, as from there the road follows sandy tracks up the Khargush Pass and back to the Pamir Plateau. We don't trust my rental bike to do this and we’re not feeling fit enough either. We decide to take a cab back to Khorog, relax there a little and then travel to Dushanbe. Unfortunately, public transport in the Wakhan Valley is very limited and from Langar there is a collective minibus back to Khorog only twice a week and we just missed it. We rely on an expensive private jeep transfer, one of many in Tajikistan. Every time it’s a real nuisance to tie the bikes properly on the roof and everything always takes a long time. We are getting tired of always being dependent on transfers, restaurants and accommodations and not being able to move freely, but something else is unfortunately not possible with a broken rear hub and thus Tajikistan turns out to be surprisingly one of the most expensive countries on our trip so far.

Farewell to the Pamir

After some relaxation in Khorog we want to continue our journey towards the capital. We will leave the mountains and the Pamir, probably the most spectacular landscape of the trip so far. But the temperatures in October are dropping lower and lower and already the first heavier snow is announcing itself in the Pamirs. It’s definitely time to move on. Dushanbe is located 600 km from Khorog and a trip by a shared jeep can take between 12 to 20 hours. We therefore decide to break this long ride with an overnight stay in Qalai-Khumb and still it takes much longer than expected.

Half of the route is on unpaved roads, only after Qalai-Khumb the road improves and allows us to move faster. Well at least theoretically, as we pick-up new passengers along the way which means we have to load and unload the luggage on the roof all the time. But there are also many mysterious short stops where some bags are handed over and a few meters later bundles with banknotes are collected. We don't try to figure out the system anymore and just somehow try to get through the long ride together with the other random passengers who are talking loudly. At some point the time has come for my most feared stop: lunch break. This usually means greasy Plov, stale bread and Shorba to choose from. I eat a few crumbs and long for a change from this diet that doesn’t suit me and keeps making me sick. I decide calling it "the revenge of the Plov". But the little girl next to me doesn't like the local food very much either and she throws up in the jeep. Once again, we have to stop and clean everything. Patience can not only be learned in meditation retreats, but also on a shared transfer in Tajikistan. We arrive late in the evening in Dushanbe and are relieved to have a few days without transfers ahead of us.

Test of Patience in Dushanbe

Before Tajikistan became a Soviet socialist republic, Dushanbe was just a village of a little over three thousand people known for its weekly market held on Monday (Dushanbe). From 1926 to 1961 the city was called Stalinabad and during this time numerous pastel neoclassical buildings and wide avenues with large deciduous trees were built. Unfortunately, the Tajik government opted for a new vision and the neo-classical architecture is mostly gone or covered up in glass and plastics and the big trees are being cut down. The once modest village is now the largest city in the country with almost 700,000 inhabitants and the contrast to the places in the Pamir couldn’t be greater. Luxurious cars drive past us, the men wear fashionable suits and we find a few expensive international restaurants and even a real bar. On the bike paths along the wide main road, women stroll slowly in small groups, often dressed in typical Tajik style with knee-length cotton tunics in colorful patterns and matching loose pants.

Of course, besides this more modern Dushanbe, there is also a big local market, small kiosks, stores with copied DVDs, restaurants with the usual greasy meat dishes and neighborhoods that remind us of the typical microcosm of villages. Nevertheless, coming from the Pamirs, it is quite a culture shock for us to suddenly be in such a modern city and although we tent to really like cities, Dushanbe isn’t our place. At this point, it’s perhaps worth mentioning that Central Asian capitals are generally not the reason for visiting the area and most travelers just spend one or two days in them before continuing to more interesting places.

We would also like to continue right away, but we have to hold out for 10 days to wait for our replacement hub. Since we hope that it will arrive a little earlier than expected, we prefer to stay in the city, even though a trip to the Fann Mountains in the west of the country would be very appealing to us. But that would mean more transfers and we don't feel like that at all. The stay in Dushanbe, however, turns out to be very unpleasant, since masses of Russians have fled to Central Asia before the mobilization and all hotels are occupied and completely overpriced. Three times we have to change the accommodation, which means each time a transfer with a taxi and the broken bicycle within the city. All guesthouses are overbooked and we can't concentrate well on the work on the website. We shift to nearby cafes and work from there and, of course, make a few forays through Dushanbe, hoping to find some inspiration here after all. We don’t succeed.

The museum without content

If the major attraction of a city consists of the former highest flagpole in the world, you can already guess what to expect from the rest. Nevertheless, we don't give up and try at least visiting the newest museum of Central Asia, which has just been opened in October 22, is not marked yet on any map and doesn’t seem to have a name either. It’s located on a completely new square, for which an entire city quarter had to give way. Of course, there are numerous colorful fountains, but otherwise the square lacks anything that would invite you to stroll around, such as comfortable seating or food stalls. Nevertheless, evening after evening, locals find themselves here, strolling across the oversized concrete square and taking selfies.

The main attraction is the museum, located in a massive column with a crown. Of course, it is illuminated at night. So much pomp hopefully promises some content. But far from it. We should’ve known better, Central Asia isn’t famous for its museums for a reason. We pay USD 7.-, an exorbitant entrance fee by local standards, and enter an almost empty building. Huge illuminated halls display a few local souvenirs and then on the second floor a model of the museum itself, of course a large portrait of President Rahmon with his bushy eyebrows and paintings of highways and power plants, the pride of the nation it seems. The museum has done a great job in representing literally nothing in an oversized building.

From the observation deck, one realizes how the city is reinventing itself and how many areas are being flattened for such huge projects. It leaves a queasy feeling, as Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries and many people have to get by with very little and live without a good power supply and then there is the whole poor infrastructure in the east of the country, which could be renewed. For example, the hospital of Murghab has no running water in the house. When you know all these things and then visit this museum in Dushanbe, you wonder where the money comes from and where the priorities of the decision makers lie.

We focus on the positive, finally eat some good food, I'm slowly feeling better and we meet two nice Swiss cyclists at the guesthouse. At some point, even the long 10 days are over and we still haven’t received our awaited package. We go to the DHL headquarters to find out, that the rear hub has been sent by the Tajik post and not by DHL inside the country and it could take another 2 or 4 weeks to arrive. By then we’re already far away. The whole situation is extremely frustrating, because we lost so much time and money in Dushanbe and now we still don't have a roadworthy bike after a month of waiting altogether and have to have a new replacement hub made, paid for and delivered again, but this time we don't have it sent to Tajikistan, but to the next destination, where we won't be for another month, so that should hopefully work out. Now nothing holds us in the city and also no more in Tajikistan and after 35 days we leave the country of the Pamir Highway with mixed feelings.

I’m very happy to continue, as Tajikistan literally hit my stomach and in general things just weren’t easy at all in this country and often very frustrating. But I also think back full of gratitude that we were allowed to experience the Pamirs for a short time and to immerse ourselves in the culture of the Pamiri people in the Wakhan Valley. Despite all these wonderful impressions, I don't want to come back again in the near future and I'm more than willing to travel on. Dario feels a bit different, because for him our Pamir trip isn’t finished yet and he can imagine to cycle the missing part some time later. But right now, we’re both just looking forward to the next country. We’ll be spending three weeks in Uzbekistan, the land of blue tiles and beautiful Islamic architecture.

Leave a Reply