Central Asia Part 5: Along the Pamir Highway via Murghab to Khorog

Pamir Highway: Cycling on the roof of the world (53)

We have a sleepless night behind us. Outside our window the majestic mountain panorama of the Pamir unfolds and we’re uncertain whether we’ll cross the Tajik border today. Never before has a border crossing made us so nervous. The border was closed during the last years and only with many special permits and the help of Shamurat, a guesthouse owner from Sary-Tash, two Australians managed to recently enter Kyrgyzstan via the Kyzyl-Art border. We are next in line, just in the other direction.

Excited and with a queasy feeling in our stomach, we’re now sitting in Shamurat’s jeep and drive over a bumpy road up the Kyzyl-Art-Pass (4280 m). On our way we’re passing horses and yaks and a few houses. Shamurat has wisely taken a bag with tobacco, Coca Cola and snacks for the border officials and thus the Kyrgyz border post is quickly passed. The road up towards the Tajik border is getting worse and it would’ve been very exhausting to cycle this way. We pass the famous ibex statue on the pass and take a few photos, but inside we feel queasy. We have no idea what will happen at the border post and whether we will be allowed to enter Tajikistan.

Corruption at the end of the world

Our jeep stops and we walk to the fence and talk to the border guards. It’s clear very soon that we won’t be allowed through. They didn't get the permission from their boss to let us enter and could get problems, as the border still isn’t officially open yet. But now Shamurat is in his element and he hands over his gifts and starts to negotiate and we also embellish our story a bit and find numerous reasons why we have to cross the border today. We try everything, but after an hour of tough negotiations it become clear that we’re not getting anywhere with logical arguments. Shamurat is taken aside by one of the border guards and then returns to us and ask us shyly if we’d be willing to pay USD 100.- for the border crossing.

Our thoughts are going crazy. We’re finally at the Tajik border after being busy with all the administration for two weeks and now we’re so close to the Pamir Highway. But then again, corruption in the middle of nowhere and we're supposed to support that? That doesn't feel right. But we’re honestly too exhausted to go through all of our options and make a pragmatic decision and we hand the money to the border guard, which quickly disappears into his shirt pocket. We’re allowed to enter, but have to promise to leave the province of Murghab tomorrow by car, so we won’t be in their district anymore. And on top of that, there's the condition that we’re not allowed to tell anyone about our border crossing up here. Of course, we quickly agree to all these terms and are totally excited when we finally see the Tajik entry stamp in our passports. All the waiting in Osh and all the efforts have paid off (pun intended).

But at the same time, it all feels wrong and we’re not sure if we made the right decision. What kind of example are we, if now all travelers coming after us also have to pay USD 100.- because of us, where does that lead to? And yet there is also this incredible excitement, because now we are actually completely unexpected on the Pamir Highway at over 4200 meters above and we say goodbye to Shamurat and slowly roll off into a landscape that is literally breathtaking.

Breathtaking Pamir Highway

We’re on the Pamir Highway, the legendary part of the M41 highway that runs through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. It’s the only connecting road through the eastern Tajik province of Gorno-Badakhshan and, at 4655 meters, the 2nd highest paved highway in the world after the Karakorum Highway. Like the Himalayas and the Tibetan highlands, the Pamirs are also known as the roof of the world. The Eastern Pamirs are located at over 4000 meters and are a completely barren landscape with only a few settlements and people who have made a living in an unforgiving climate.

The Pamir Highway was completed in 1932 by the Soviet Union as a gift to the remote region, and its proximity to Afghanistan and China gives it the aura of an adventure route. The highway is a legendary destination for many intrepid travelers, a small number of long-distance cyclists, more leather-clad motorcyclists on monster machines and even more 4x4 heroes have always been attracted to the lonely mountain landscapes and the hospitality of the people along the 1250 km route from Osh to Dushanbe.

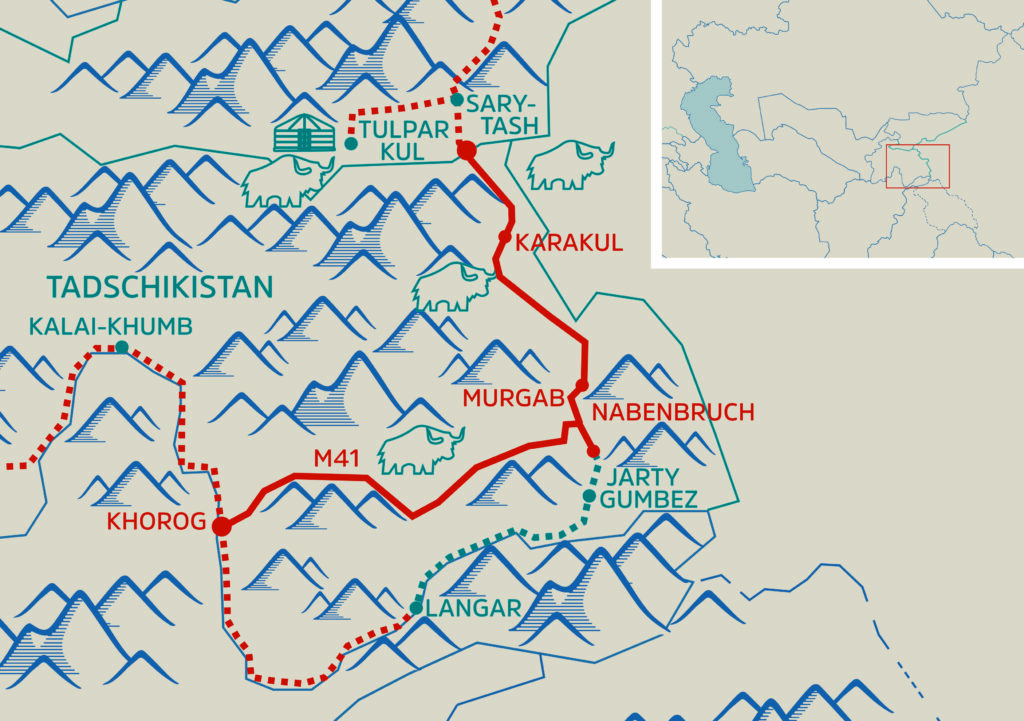

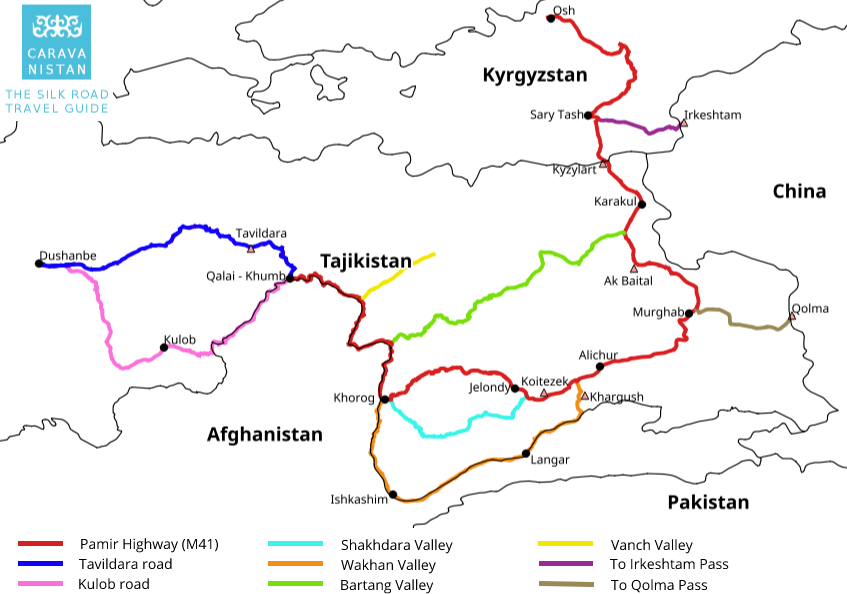

However, most of them don’t just follow the M41 (red line), because there are numerous scenic secondary routes, which are also very interesting. The route along the Afghan border in the Wakhan Valley (orange) is particularly popular, and the rarely cycled Shakhdara Valley (light blue) is also said to be very beautiful. If you are looking for real adventure, you can also venture into the wild Bartang Valley (green), where you have to be prepared for even more bad roads, river crossings and the feeling of true remoteness.

A trip along the Pamir Highway shouldn’t be underestimated, no matter the means of transport. You have to come prepared and it’s not for everyone. Traveling along the Pamir requires a lot of patience, commitment and dealing with lack of comfort & hygienic food, but in return you’ll be rewarded with views, insights, encounters and experiences that are probably unique. Few regions on earth offer an experience as far from civilization as the journey along the eastern Pamir Highway.

The landscape is characterized by the forces of nature, ice and water. The extreme climate is cold and dry all year round, with freezing temperatures in winter and mild temperatures around 20° C during the day in summer from May to September. The lack of precipitation limits plant growth to hardy shrubs and few trees, only the lower valleys have more vegetation, but for the most part the Pamirs resemble a barren desert. In the inhospitable and sparsely populated areas and in the unforgiving conditions of the Pamirs live only a few animals like wolves, marmots, the endemic Marco Polo sheep, wild rabbits, snow leopards and a few wild camels. As we cycle we keep seeing rabbits and marmots, but the imposing Marco Polo sheep keep hidden. To our left is a mile-long border fence with China, which is permeable in certain places. How easy it would’ve been to just walk through. We’ve never been so close to China.

Lonely landscapes, hard everyday life and our highest pass

As we cycle our first kilometers on the Pamir Highway, we can hardly believe our luck. How big is the coincidence that exactly we are allowed to be up here where almost nobody has been for years? The whole situation is completely surreal and the landscape alone invites us to hallucinate, even without the emotional roller coaster ride that is hitting us. We can't continue cycling, we have to sit down first and let the whole thing settle. We keep looking at each other in disbelief, we are here, we are here!!!

How long have we dreamed of this road and now the time has come. And the landscape around us is so spectacular, so gigantic, that we can't find any adjectives which do the scenery justice. The Pamir leaves us speechless from the first moment.

We’ve already seen many spectacular landscapes on this trip such as Cappadocia in Turkey or the Lut Desert in Iran, but somehow the Pamir is even more extreme than anything we’ve seen so far. Just knowing that we’re the only people far and wide and that we’ll encounter not a single soul on this stretch from the border to Karakul. We’ve never felt so far away from everything and everyone. It's a liberating and sublime feeling, but one that also comes with a lot of respect for the rugged mountain world. For the first time we’re cycling at an altitude of over 4000 meters and we’re worried about altitude sickness and have to plan our daily stages carefully so that we don't have to spend the night too far up.

Our destination for the first night is the village of Karakul at the Karakul Lake at 3960m. We see the village already from far away and are surprised that there is nothing in front of the actual settlement. Not a single hut, no farm, no herds of animals, no store, simply nothing. We’ve never experienced this before. The village really begins with the first house. Remote Karakul is inhabited year-round by Kyrgyz, like so many places on the Pamir Plateau. It will be a few more days before we have our first encounter with the friendly Tajiks. In Karakul we just see several water pumps and a whitewashed mosque, but there’s no supermarket around. We’ve got enough supply to cover some distance, but don’t want to start using it right away and so we decide to stay in a homestay and save our food for later. Along the Pamir there are only a few hotels and unfortunately no more yurt camps. The nights are spent in homestays with families, where you’ll also have your dinner and breakfast usually.

We find this network of homestays a great idea, as we get to support the families directly by staying with them. An overnight stay in such a simple homestay incl. breakfast and dinner costs between USD 15.- to USD 25.- per person, depending on the remoteness and the comfort offered. Our first homestay, the Sadat Homestay in Karakul, is really cozy and we have a room for ourselves with two narrow beds with thick blankets. Only for the toilet we have to dress thickly at night and scurry out across the street. We have to get used to that here. But you don't come to the Pamirs because of the comfort and when you see how the locals live up here, then you become quite humble and modest with your own desires anyway. Life here is brutally harsh and there aren’t many options, not many influences from outside and not many opportunities. It doesn't help if the surroundings are incredibly beautiful when the weather is good.

Only when we take a walk through the village the next morning, we start realizing that we’re actually on the Pamir. We promised the border guards that we would take a cab to Murghab right after our arrival in Karakul and leave their jurisdiction as soon as possible, but we want to continue traveling at our own pace and experience these epic landscapes on our bicycles. However, when we see the border officials from yesterday passing through in the car, we get a lump in our throats. They look at us all stern and then continue driving. We breathe a sigh of relief. We are lucky. Probably there won’t be any consequences for us and they just don't want the rest of Tajikistan hearing about their bribe scheme.

Back at the homestay we meet two Finish cyclists, who of course ask us where we come from. Apart from Murghab, there are only two other possible ways to reach Karakul: Either through the wild Bartang valley or from the Kyrgyz border. And we can’t lie to them and tell them about our border crossing experience, as they also plan on crossing into Kyrgyzstan. They don't even seem that surprised, because they too have already contacted Shamurat and word has spread on the Pamir that he can help with the exit across the border to Kyrgyzstan. But not only Shamurat gets a certain fame this summer, it also hits us. Again and again, we come across travelers who’ve heard about an ominous couple that was able to cross the border to Tajikistan by bike.

We leave Karakul and cycle over washboard roads and are surrounded by impressive mountain landscapes in beautiful autumn weather. Ahead of us lie 130 km of loneliness. We pass just two inhabited huts on the road between Karakul and Murghab. A Kyrgyz family spends the summer months up here with their yaks. We stop and visit them in their modest hut. They all live together in a big yurt, the young parents, the two children and the grandfather. In the winter months they return to Karakul. I can't help but look at the pretty young mother with her traditional clothes and braided black hair and wonder how her life would have been in a completely different place. Already Osh seems much more than just 280 km away, but a whole other planet. That's how far away we feel here.

Living in this harsh climate takes a level of resilience that few of us could ever understand. Spending months in this simple hut up here in this unforgiving climate feels like the complete other end of the hectic life of Western Europe, where one’s always looking for optimizing every aspect of life. Completely different everyday worries and considerations characterize the daily life in this inhospitable place. And yet we are united in our hearts. During this trip we learn to focus much more on the similarities between people instead of the differences.

The grandfather sits behind a primitive device with which he separates the cream from the yak milk. We are served bread with fresh yak cream and yak yogurt and rarely have such simple dishes tasted so good. The ideal strengthening for the upcoming pass and still days later we will rave about this meal. It’s a special encounter for us, but we can't dwell on our thoughts for long, because ahead of us is the Ak-Baital Pass (4655 m), the highest pass of the Pamir Highway. We have problems breathing and can only move at a very slow pace and at some point, we actually stand as high up as never before on our trip and are amazed about what is possible with our own physical strength. However, an icy cool wind makes us leave the pass quickly.

On the other side, the landscape remains barren and stunning. A few empty houses along the way serve as a perfect windbreak for our first night in the tent on the Pamir. The wild camping experience is amazing on the Pamir and you can pitch your tent everywhere you like. It’s one of the best things about cycling the Pamirs in our opinion. The cold shower is difficult, but we can sleep quite well despite the altitude and seem to have no problems with altitude sickness so far. And then there are the stars. Only the deserts of the world can compete with the starry nights in the Pamirs. When we get up the next morning and look around us we see no sign of life, absolute silence surrounds us. These first few days on the Pamir are just fantastic and we can’t stop marveling at the harsh beauty surrounding us.

Murghab: No place to linger

On the fourth day we reach the first real settlement in Tajikistan, Murghab. As the only settlement for a long time, this pioneer town is an essential pit stop on the Pamir Highway. A forgotten outpost in the eastern Pamir mountains at 3600 m above sea level. 10'000 people live here, in winter at - 40 ° Celsius and several hours or days away from the next town Khorog via bad tracks. Our first impression? There is a Wild West atmosphere with stores in shipping containers. We take a stroll and cross a woman who is bringing two bleeding sheep heads into her house. Children with neat school uniforms and snotty noses marvel at our bicycles and happily pump water for us from the public wells. Fortunately, we always have a few sweets in stock for such cases.

50% Tajiks and 50% Kyrgyz hold out in Murghab and they seem content living so far away from everything. The pretty whitewashed houses with blue shutters give us a feeling of Greece in the middle of nowhere. But the biting cold wind chases away our daydreams and despite the beautiful weather Murghab seems to us extremely desolate. A place to write a novel, if one had the stamina to linger. But actually, one just wants to leave immediately.

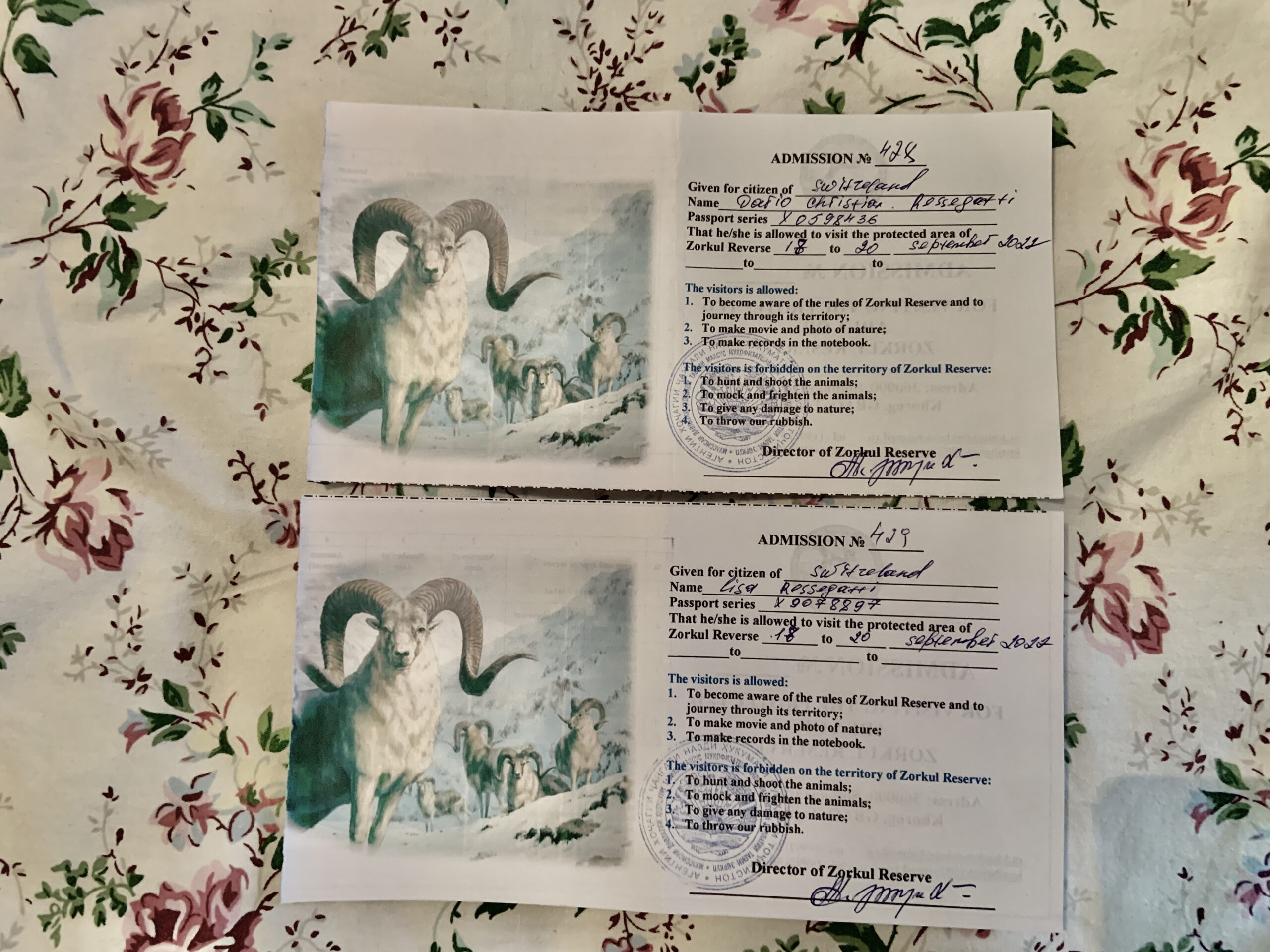

Along the main street there is the usual ensemble of representative buildings with the portrait of the eternal president Emomalij Rahmon (since 1994!) on the outside wall. Kyrgyz with the typical high Kalpak hats ride their bikes to the bank, Tajik women with flowered headscarves buy fresh yak butter and a few fashionable young women with good English skills help us to get a SIM card and the necessary permit for the Zorkul National Park.

But of course, that wasn’t as easy as it may sound, as we first had to go through the usual Central Asian routine. This means being directed from building to building and nobody feels responsible, while you slowly lose your patience, but hopefully never your humor. Especially important for us today as we get directed to a new building, still looking for the right office, and are then shoveled into a room and find out that we just arrived at the newest museum of Murghab: the museum for the majestic Marco Polo sheep. Full of pride, we are led into the only room with its stuffed animals from the local fauna. A man is just unpacking the LED lamps. We have to laugh at the humor of the situation and try our best to look at the exhibited animals with awe. We wonder if the museum will make it into the new edition of the Lonely Planet. Shortly after we are finally guided to the responsible person and get our permission to visit the remote Zorkul Reserve. What a day.

Check-in at the Hotel Pamir. The most noble option in the Eastern Pamir. Power sockets, a proper bed and a private bathroom with carpet on the floor (!). Internet? Extremely moody. We take a break day and stock up our supplies and cook ourselves, because the food in the hotel and the few available restaurants makes us sick. In Murghab, the way to a man’s heart is definitely not through the belly. There are huge portions of tasteless chicken and greasy fries, bland soups with an indefinable meatball and stale bread. The shops in the shipping container bazaar also only have a sad selection with loads of candies, cheap clothing and just few fresh products. After looking for several hours we return to the hotel with just a large pumpkin, carrots, onions, apples and pears. That must be enough fresh products for the next week, more is not available here. We will also have to get used to the stale bread and during our 35 days in Tajikistan we get to taste fresh bread only twice. Whenever the official bread baking day is, we seem to miss it during the whole time. If someone could solve this mystery for us, we’ll be very happy.

As a cyclist, you have a tendency on longer stages in remote areas to hype up the next bigger town by saying things such as: "When we finally get to XY, we can go to a good café again, we can drink a cold beer, shop in a big supermarket and there are several restaurants to choose from." This motivates and this anticipation is extremely important for morale. But on the Pamir Highway, that anticipation is limited to things like "apparently there's a well in the next village and we can fill up our water supply again." We’re honest, it’s not easy and we start missing very simple things.

Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in the world. Since Tajikistan's independence, civil wars and the struggle for independence have characterized the province of Gorno-Badakshan. Violent unrest has repeatedly erupted in the autonomous province, and the government shut off the Internet for several months, leading to ethnically motivated mass arrests. Poverty and territorial insecurity slowed progress until China began its policy of expansion into the West and opened the borders to trade in 2004. Since then, trucks have been rolling in both directions and China invested 2/3 of Tajikistan's GDP in recent years. The new trade route snapped the country out of its long isolation and change is on the horizon. Nevertheless, extended families, close community and mutual aid are highly valued and the Pamiris are famous for their hospitality. The young people are well educated and clearly oriented towards China, learning Mandarin rather than English. If you’d like to get an insight into life along the Pamir, we can recommend this documentary: Dream Routes Pamir.

End of our bike trip in the middle of nowhere

We are relieved to be leaving Murghab after two days. We have our permit for the Zorkul Reserve in our pocket and are looking forward to this special route. The plan is to leave the main road after 30 km and follow a small gravel road to the hamlet of Jarty Gumbez and from there continue to the Zorkul Nature Reserve, home of the famous Marco Polo sheep and wild Bactrian camels. This complete solitude in a place that is already very remote appeals to us and, of course, the challenge. After all, we’ve been dreaming of such adventures from the comfort of our couch for years and now the time has come.

As we turn off the M41 highway, we feel like we’re on a real adventure for the first time since we left Switzerland. It’s incredibly quiet around us and we see no traces of civilization far and wide. Only now and then a few wild rabbits scurry through and then it gets cooler and cooler and it starts to snow and the visibility gets worse. We’re not excited to camp in these conditions and are happy when we discover an abandoned shepherd's hut on a small hill. The hut is surprisingly tidy and has two rooms, although no windows. Around the hut lie the impressive horns of Marco Polo sheep. In winter, unfortunately, the majestic sheep are being hunted by wealthy foreign tourists. We pitch our tent in the larger room, unpack the camping chairs and cook a delicious meal, looking out every now and then, who knows, maybe we'll see a snow leopard?

It’s this absolute solitude that we were looking for on this trip. And as much as this must sound like romance and adventure, we have to admit that it’s also a mental challenge and not easy to deal with this loneliness. With the distance to other people also grows the respect for the unpredictable nature and the knowledge that we would be lost in case of illness or accident. It’s not easy to put these thoughts completely aside and of course there is still the altitude, because we are now regularly camping above 4000 meters.

The next morning a small snowstorm awaits us and it’s quite unpleasant as we continue cycling towards Jarty Gumbez. There are supposed to be some hot springs and thinking about them motivates us to continue in this harsh weather. But then suddenly I feel that something is wrong with my rear wheel. Several spokes are loose and then I discover the problem: the rear hub is broken. This is a defect that we can't fix ourselves, we need a completely new rear hub. We realize within a few seconds that this means our bike trip is over and we can't continue cycling on the Pamir Highway. Our dream of the Pamir is suddenly over.

And then the impossible happens at the most remote place of our trip: two cars with Japanese tourists pass by. Probably the only traffic here for days. We have no time to think and stop them and ask them to take me and the broken bike to Murghab. There we might have internet access and the possibility to organize everything else. They agree and take me with them, but they don’t have space for Dario and he decides to cycle back to Murghab and gives me his bags. Only during this ride, we both start realizing what just happened.

Lisa's thoughts in the jeep and back in Murghab:

During the journey my thoughts circle incessantly and my head whirls. What does it mean now, how do we go on, what should we do? In such moments I just function and try not to let the emotions get to me. I'm just grateful that in the middle of nowhere we miraculously found help. At the same time, I blame myself a little bit, because I cursed a few times about the bad food, the tough roads, the exhaustion and the remoteness of the Pamir, but I never wanted the journey to end so abruptly. Is now Karma coming back at us because we bribed our way into the country?

Unwillingly I'm back at the Pamir Hotel with the carpet in the bathroom and the moody internet and while I wait for Dario I try to plan the next days. It quickly becomes clear to me that we have to leave Murghab as soon as possible, because in the last few days there have been shootings at the Kyrgyz and Tajik borders and rocket launchers are already being stationed in the border town of Sary-Tash. This is the border that we just passed a week ago. All of this is somehow eerie and I don't want to linger on the Pamir Plateau any longer, as spectacular as it is.

But with a simmering border conflict lurking around the corner, all I want is to get back to civilization where we have more options for action. Add to that the generally unstable situation with masses of Russians escaping the military mobilization to Central Asia, a renewed conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh in the Caucasus, and then of course the wave of protests in Iran. It's a turbulent time in September 22 and it's hard not to be influenced by it. And at the same time, world events again put our own problems into perspective like a broken rear hub.

Dario's thoughts while cycling back to Murghab:

Suddenly I am all alone, in the middle of this vast and deserted landscape, 20 km away from the Pamir Highway and 50 km from Murghab, in the middle of nowhere. And when a bitingly cold wind comes up, the freezing rain hurls against my cold cheeks and I realize that I can't just put on warmer clothes, because all my luggage was with Lisa in the car, I suddenly feel very small and vulnerable. But then I tell myself that I just have to keep cycling, then I would surely not freeze to death and sooner or later arrive in Murghab. So nothing can actually happen to me, and with this realization I pedal even harder. At times also too strongly as I’m completely shaken by the washboard road.

I struggle to get back to the Pamir Highway on this bad gravel road. When I arrive at the main road I suddenly start to realize: This was it with cycling on the Pamir, because this means we’ll never get to see Jarty Gumbez, a place we know from videos of other bike travelers, which is so remote that we haven't even found it on the map for a long time. And we will never soak in the hot springs there. That’s almost the most painful part for me at this particular moment. I’m struggling with our fate, we had invested so much time and energy to be here now, at one of the highlights of our trip. And why does something have to break here that we can’t fix ourselves, out of all places, why on the Pamir?

Apart from the usual flat tires we almost had no defects on our trip so far, why now and something like that. Why could not just break a spoke, as other cyclists experience it regularly? We’re equipped for various situations with plenty of spare material, but of course we’re not carrying a spare rear hub with us, why should we? With these questions I torture myself over the Pamir Highway and at the same time fight with the strong and cold headwind. I want to reach Murghab as soon as possible to help Lisa, because there’s a lot to organize and she surely worries about me.

In the late afternoon we’re finally reunited in the warm hotel room and book a taxi transfer the next morning to Khorog, the provincial capital in the Pamirs. There we will hopefully have more stable internet and be able to plan everything else. Much faster than expected we will now leave the Pamir plateau. Only just 10 days were granted to us on the legendary Pamir Highway, although completely unexpected.

Just an ordinary taxi ride on the Pamir Highway

Tales of the Pamir. A jeep ride to Khorog sounds simple and much more comfortable than cycling, but even this can turn out to be quite an adventure. The originally planned private transfer for us and the broken bike to Khorog turns into a trip with numerous passengers regularly getting in and out. At first there are only our bikes and luggage on the roof, but shortly afterwards also a bag full of meat and then a very lively goat, which rides in a very uncomfortable position on the roof for hours and grumbles pathetically as soon as we stop. Shortly before Khorog, the goat is handed over to a local, fate unknown. Also along for the ride is a funny geologist who gets off in a former Russian sanatorium in the middle of the M41. Quite enthusiastically, he keeps commenting on the mountain panorama left and right, and we show him pictures of the comparatively small Swiss Alps. We’ll never forget his pitying look when we tell him that our highest mountain just measures 4634 m.

Two young students are also in the taxi with us. One of them works as an English teacher in Khorog and was just visiting his village where he took care of his 60 yaks. He is warmly greeted by his friends in Khorog. Even the bulky guy on the passenger seat, who empties more than three liters of beer during the trip and soon throws his pumpkin seeds into the jeep instead of out of the window, is lovingly embraced by his mom in Khorog. And of course, we can’t forget to mention our driver, who keeps referring to himself as gangster and comes with a whole set of gold teeth.

Our mixed group arrives well in Khorog after an 8-hour drive and we’re thankful that the jeep didn’t break down and everything went well. Much too soon we are surrounded by mild autumn weather, many people and stores and fall exhausted on our cozy hotel bed in Khorog. This is not how we imagined our Pamir adventure would look like.

The last months have taught us to deal with such tough situations and to look forward and be grateful for everything we were allowed to experience so far. Never would we have thought that we would actually get to ride the Pamir Highway this summer and experience such lonely and majestic landscapes by bike. Most of all we're just incredibly grateful. But our Pamir adventure isn’t quite over yet and in the next blog we will tell you about our ride along the Afghan border.

[…] We are in Khorog (30'000 inhabitants), the capital of the Autonomous Province of Gorno-Badakhshan in Tajikistan. We’re now back in lower altitudes at just over 2000 m and are experiencing pleasant, mild autumn temperatures and blue skies. It’s already a huge contrast to the barren Pamir plateau where we’ve been traveling the last few days. We were actually looking forward to Khorog, because there is a range of restaurants and nice homestays. But we would’ve been much more excited about reaching this little town, if we’d cycled all the way here. However, the hub break in the high mountains of the Pamirs made this impossible and so we had to take a cab from Murghab to Khorog (read more about this adventurous trip in our last blog No. 53). […]